Book Mistress Becomes a Slave Again

White Women Prospered on the Brutality of the Slave Economic system

The Mistress's Tools

White women and the economy of slavery.

Past 1836, Sarah Barnes had go something of an Alabama magnate. She endemic a domicile, land, rental backdrop, 10 stocks in a local depository financial institution in Mobile, and 27 enslaved people. On the eve of her marriage to Dennis Welsh, Barnes drew up an antenuptial agreement, a legal certificate outlining the terms of their wedlock. In it, she stated that she would continue to have "sole, entire and exclusive employ, benefit, and enjoyment" of her property. All of the rent collected on her real-manor holdings would go on to go to her, every bit would any potential wages earned by her enslaved people rented out for their labor. Barnes engaged a trustee, Richard Redwood, to aid her manage her holdings, just he was allowed to take action only if she delivered him written instructions, produced in the presence of "six reputable persons and in the absence" of her married man-to-be. She also reserved the right to make her ain will, which was to be fatigued up in the presence of four people—1 of whom had to be a clergyman—and then signed, sealed, and published then that Dennis could not alter its terms after her death.

Six reputable persons? A clergyman? What can account for Barnes's exacting enumeration of her property rights and her palpable worry about her time to come husband'southward meddling? She knew that when she married Dennis Welsh, she would become, in the parlance of the period, a "feme covert," or a covered woman. She'd lose the right to bring adjust, make contracts, and own belongings. All of it, her small empire of fields and flesh, would become his. And losing her enslaved people—this would exist the bitterest pill of all, because in these people, and so much of her wealth resided, and in the ownership of them, so much of her power. Her antenuptial understanding marked her refusal to give them up.

This is a remarkable, appalling document. Information technology is an archive of a woman who navigated a legal organisation designed to exclude her, in a state where she wouldn't be able to vote for some other 84 years. And yet, there is absolutely aught feminist nigh this document, because while it may bear the imprint of a woman who bankrupt with common law and gender expectations, it simultaneously exposes why she did and then, and at whose expense. Barnes doubled down on slave ownership, embracing white supremacy as a ways to overcome her disempowerment on the basis of gender. Her opposition to patriarchy and her subjugation of black people were one in the aforementioned; in fact, they were mutually constitutive.

Barnes was not alone in using slave buying to gain back some of the coin and ability allotted to her under patriarchy. The historian Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers's They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South is a definitive account of how deeply invested white women were in the slave economy of the South. Jones-Rogers's book is a compendium of the actions taken by white women to preserve the wealth they had in human flesh every bit theirs alone. It scrupulously dismantles any image of slave-owning women as somehow less involved, less culpable than their male person counterparts. Jones-Rogers also makes a instance for why these slave-owning women were so motivated to protect their status equally slave owners, and her answer has to practise with the racial logic of capitalism.

Recent studies of the economics of slavery accept shown that plantations were financially unstable places—bankrolled on credit, often intractably in debt, and subject field to the perennial busts of the system of transatlantic commercialism, of which plantation slavery was a crucial part. For women, Jones-Rogers argues, independent wealth represented a bulwark against the financial risk their husbands assumed when they played the speculative cotton wool market. Should all be lost, at least their coin would be safe; and so would their condition—as ascendant people. Slave ownership provided white women with a machinery for joining their male person counterparts in the ruling class, which might otherwise accept been closed off to them. Wealth and racial domination could become them at that place. Thus they (quite literally) capitalized on their whiteness to proceeds power, and they did so at the devastating and ongoing expense of black people, and blackness women in particular.

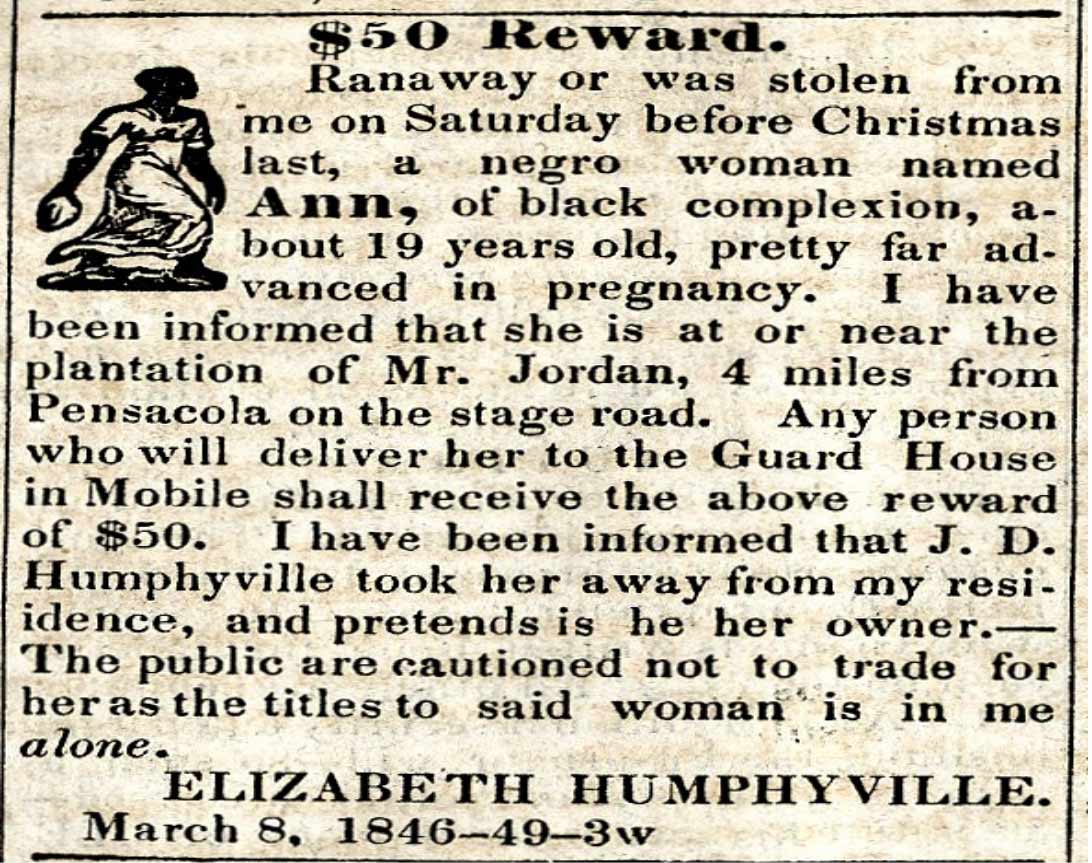

Elizabeth Humphreyville's runaway ad for Ann, Pensacola Gazette, March eight, 1846. (Nineteenth-Century U.South. Newspapers database, Cengage/Gale)

"Her presence fabricated the plantation a home; her absence would have made it a manufactory," wrote the historian Ulrich Bonnell Phillips of plantation mistresses in 1918. In Phillips's account, the white mistress assumed the double responsibility of tending to her white children and to her black charges as well. She worked "with a never flagging constancy…. served as caput nurse for the sick, and taught morals and religion past axiom and example." She was busy, as the plantation's domestic manager and moral authority. Phillips's then-influential account of the plantation household recapitulated the image of the white mistress promoted by the Lost Cause propaganda of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow Due south—that plantations were more often than not happy places, thanks in no small function to the kindness and civilizing influence of white women.

This image of the kind, industrious plantation mistress has had a long life in representations of American slavery. Information technology has bred a series of interrelated falsehoods, including the notion that mistresses were less physically violent toward enslaved people than were masters, and the myth that mistresses had clandestine alliances with enslaved women because they shared a similar kind of suffering under male authority. This latter falsehood gained currency amidst women and feminist historians of the middle and later 20th century—Anne Firor Scott and Catherine Clinton, for example—who prioritized the category of gender over that of race in examining power relations under slavery. Some academics saw plantation mistresses as and so constrained by patriarchy that they adult a more general critique of the subjection of women, both white and blackness, even if women at the time couldn't speak about information technology. They were, the story went, "silent abolitionists."

Historians and artists have been working to correct this faux and sanitized view of plantation mistresses, and Jones-Rogers'southward They Were Her Property is part of this motion. Her study builds on the work of historian Thavolia Glymph, whose groundbreaking book Out of the House of Bondage (2008) showed that white women harassed, beat, maimed, tortured, and killed enslaved people with as much brutality—and dispensation—as white men. Mistresses categorically sided with masters, not with slaves, particularly when it came to the administration of violence. Jones-Rogers's work also aligns with recent representations of slavery in popular media and historical fiction, which have revised their portrayals of white women every bit the myth of a special feminine compassion has begun to be dismantled. Here, one might recollect of the distance between Scarlett O'Hara of Gone with the Wind and Mary Epps of 12 Years a Slave.

Jones-Rogers continues to fill in the fierce picture set out by these revisionary—which is to say, accurate—representations. She writes, for instance, of ane woman who elected to whip enslaved people with the nettle-weed branch rather than the cowhide whip because the nettles burrowed under the skin and left a long-lasting burn—but did non scar, and thus did not decrease the person'south value. And herein lies the greatest innovation of Jones-Rogers's volume—to show that the ability white women wielded over enslaved people, reflected in horrific violence, extended into the economic structures of slavery. They engaged in roughshod acts with the logic of the market in heed. Hers is the first book to isolate white women every bit economic actors in the slave system, and thus the kickoff to dismantle some other long-standing myth about these women—that they simply stood by as men conducted the business of slavery.

Each of the book's chapters takes shape around a different economic theme, and some are titled with quotations past a formerly enslaved person, who poignantly and summarily dismisses any false notion of white-women's passivity: "I Belong to de Mistis," "Missus Done Her Own Bossing," "That 'Oman Took Delight in Sellin' Slaves." Taking her lead from these firsthand accounts, Jones-Rogers so supplies a stunningly voluminous annal of legal documents, newspaper articles, advertisements, letters, diary entries, plantation ledgers, and records of sale, which she mobilizes against a century of received historiography.

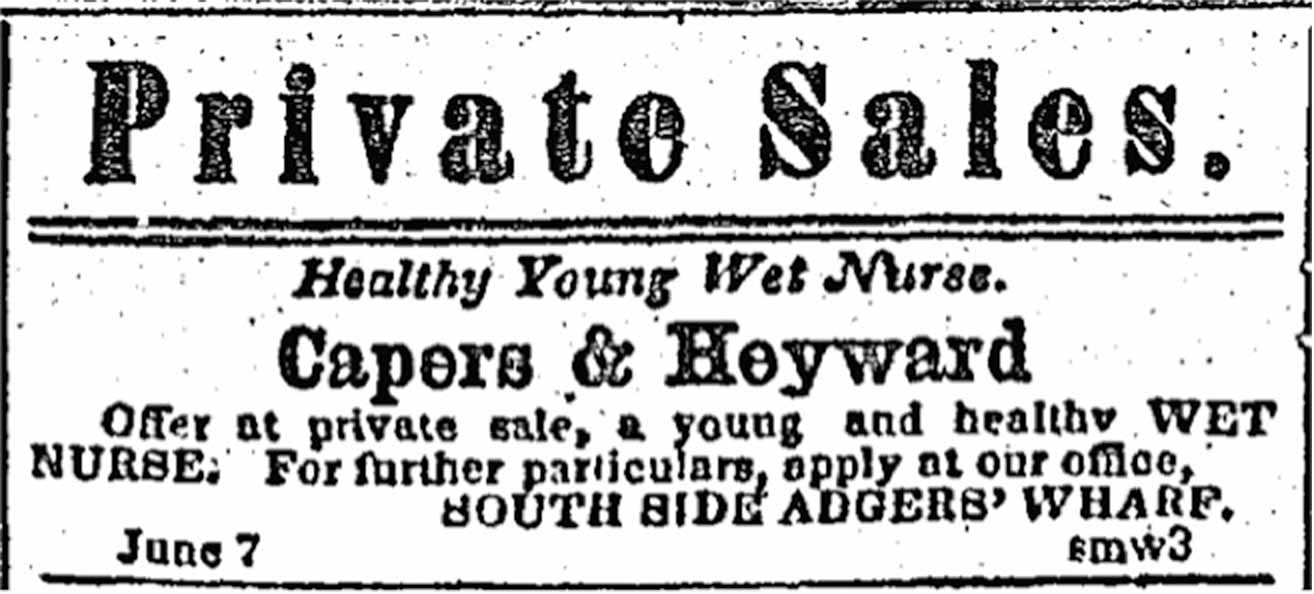

Capersand Heyward newspaper ad for private auction of enslaved moisture nurse, Charleston Mercury, June seven, 1856 (Nineteenth-Century U.S. Newspapers database, Cengage / Gale)

One of these economic fictions is that white women, even if they owned enslaved people, did not fully participate in the buying and selling of them. Many have believed that the public slave marketplace was the domain of men, bold that gendered codes of decency kept women out. Not only did white women announced at public auctions, where they participated in dehumanizing acts of inspecting black bodies, but the slave marketplace oft came to them. White women bought and sold enslaved people in their parlors and on their front porches. It is false, Jones-Rogers explains, to split the plantation S into private and public spaces. Households were the locations of slave markets, also.

Jones-Rogers also stresses the ways in which white women strategically invested in the reproductive lives of black women and intervened in their sexuality for profit. The reproductive capacity of black women, and the fact that children inherited their legal status equally free or enslaved from their mothers, made many white female owners come up to see enslaved black women as meliorate investments. With each baby born, their wealth grew. White parents were thus more likely to give their daughters enslaved women and girls, and slave-owning women made information technology a signal to continue female slaves for their households. Jones-Rogers documents cases where white women orchestrated the rape of their enslaved women in acts of forced breeding. She implies, besides, that white women were often responsible for bringing enslaved girls into households where they were systematically raped past their male masters—a system that Harriet Jacobs, an enslaved adult female who lived under the sexual menace of her male master and the psychological torture of her female person mistress, described equally ingeniously designed and then that "licentiousness shall not interfere with forehandedness."

By the onset of the Civil War, white slave-owning women were so attached to the institution of slavery that they went to great lengths to keep their enslaved people in chains. When enslaved people fled their plantations during the war, women took out fugitive-slave ads in newspapers, wrote messages to military officials, or appealed to male person relatives for assist in recapturing them. Some fifty-fifty hunted them down themselves. When they were unable to retake possession, they appealed for compensation for their financial losses. Since the Emancipation Proclamation did not liberate people enslaved in the edge states that stayed loyal to the Union (Missouri, Maryland, Kentucky, Delaware, and later W Virginia), white women living in these states appealed to the US government—not the Confederacy—for the return of or compensation for their enslaved people, even after 1863. Some went to further extremes, uprooting and marching their enslaved people outside the Spousal relationship's accomplish (called "refugeeism"), chaining them in cellars, or locking them up in prisons to stop them from fleeing.

These accounts highlight how desperate white women were to maintain legal and physical command of their enslaved people, fifty-fifty as a cataclysmic war over their right to do so unfolded. They had accrued neat wealth and social standing, and they had done so by embracing white supremacy. Jones-Rogers shows that white slave-owning women in the South did not fight racial patriarchy. Because the system was open to them on the footing of whiteness, they joined it. They wouldn't let it go. They Were Her Holding is a story of white women attaining power, and the volume makes it undeniably clear that at that place is goose egg inherently feminist or liberatory nigh the mere fact of women gaining power. It reminds us that we must always inquire: power of what kind, and at what price?

Source: https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/stephanie-rogers-they-were-her-property-slave-south-civil-war-book-review-history/

0 Response to "Book Mistress Becomes a Slave Again"

Post a Comment